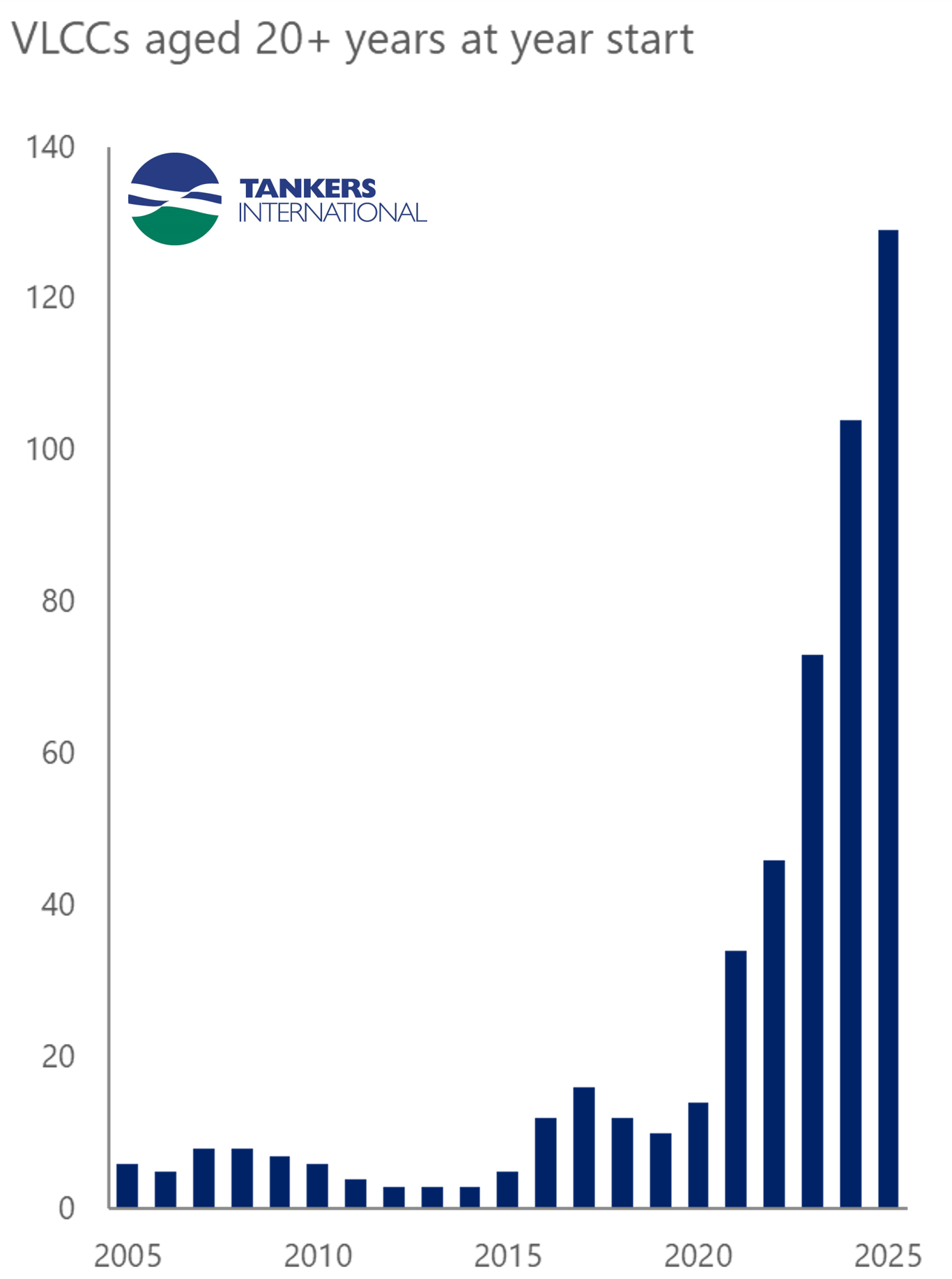

The VLCC market is going through some significant transitions. While we have technically seen the overall number of ships in the fleet increase thanks to newbuilds combined with older ships not retiring, the older tonnage is increasingly less efficient, which is actually slowing down the effective growth of the fleet. This is further complicated by the rise of the “dark fleet,” where older ships are finding work in less regulated areas, often carrying oil from countries under sanctions.

Traditionally, VLCCs were typically retired around 18-20 years old, often scrapped or converted for storage. But things have changed. These older ships now have a new lease on life thanks to less regulated trades, especially those involving sanctioned oil. This has reduced the number of ships being removed from the fleet, and many are still operating well beyond their typical lifespan. It is now normal to see trading vessels aged up to 25 years.

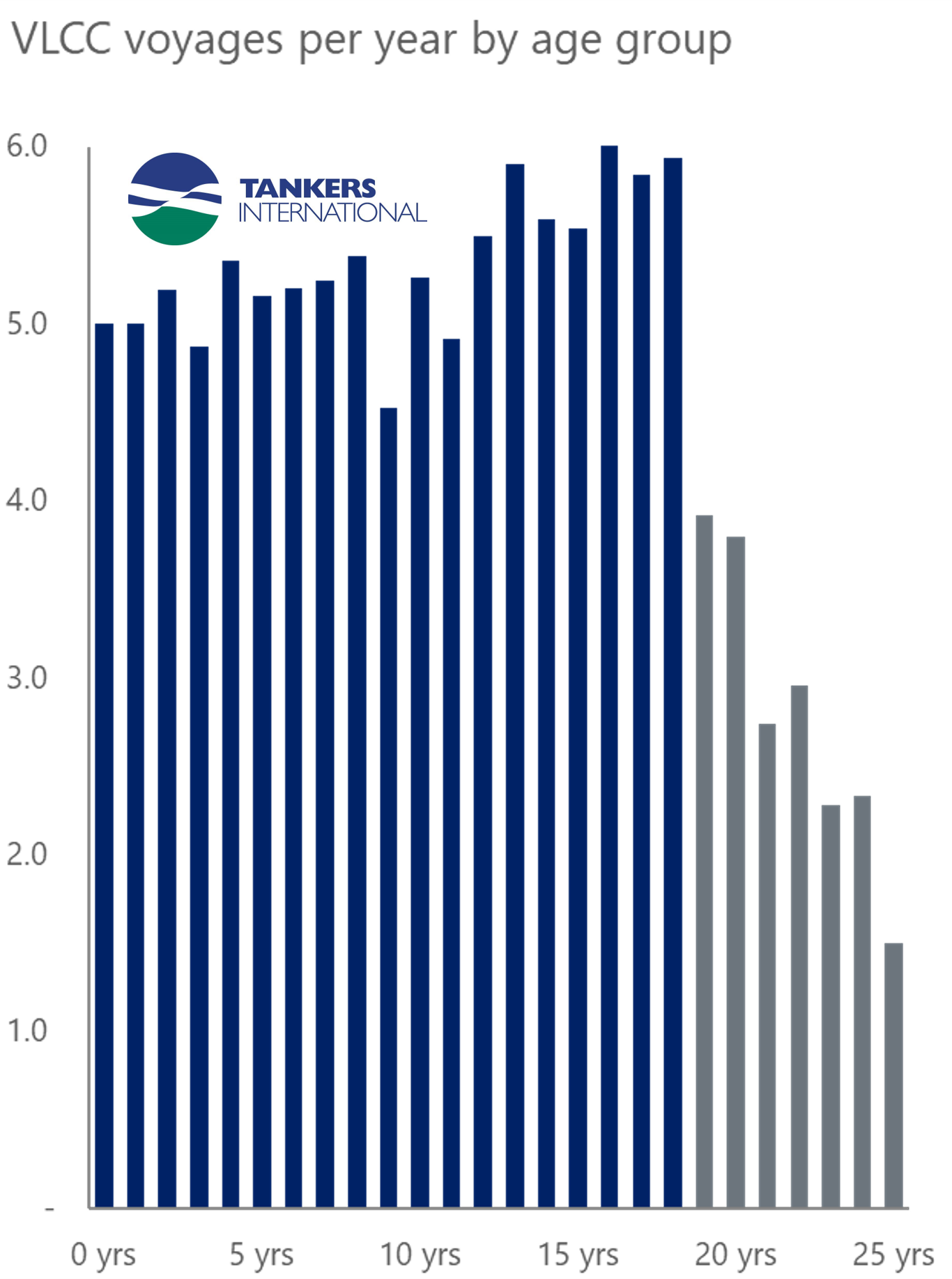

Although these older ships can still operate, they are not as efficient as their modern counterparts. Our data shows that VLCCs up to 18 years in age, usually complete about 5 voyages a year. Younger ships often load in the Atlantic Basin, where terminal and charterer regulations are stricter and voyages are longer as many discharge in the Far East. But as ships get older, they tend to be booked for shorter routes from the Middle East to the Far East, allowing them to increase their voyage count to closer to 6 per year.

After 18 years, the decline in efficiency really kicks in. Our analysis suggests that older ships (between 18 and 25 years old) lose about 10% of their utilisation capacity each year. This drop is even sharper when we look at ships not involved in sanctioned trades, with their utilisation quickly dwindling to almost zero by the age of 20 due to their lack of mainstream charterer acceptance.

This ageing fleet has had, and will continue to have a significant impact on the industry. In order to understand the true state of the market, we therefore need to look beyond just the number of ships and consider other factors – for example, age, trading patterns and operational efficiency. While the nominal number of VLCCs has increased by over 100 units in the past five years, the growth in effective capacity, considering the declining utilisation of older ships, has been much lower, around 60 ship equivalents.

Looking ahead, this trend of declining effective capacity is not going away anytime soon. Even with new ships being built, the ageing fleet will continue to put a drag on effective supply growth. With 68 new VLCCs expected to be delivered in the next three years, we are looking at an 8% increase in nominal VLCC fleet capacity. However, due to the declining utilisation of older ships, the actual increase in effective capacity will be much smaller around 1%.

The result of the growing age imbalance is that the VLCC market faces a prolonged period of supply tightness, with competition for available tonnage intensifying, in particular in the mainstream market. This market tightness could likely result in an upward trajectory for freight prices.

Watch this space for further analysis as this plays out.